In the winter of 2018, I studied abroad in Paris, France for 6 weeks as part of the CIEE Open Campus Program. It allowed you to live in 3 different cities over the course of a semester, with 6 weeks in each. I studied in Paris, Madrid and Berlin.

When I chose my arrangement of cities, it was actually Madrid and Berlin that I really wanted to go to. Madrid, because it was the only Spanish speaking city, and I had been studying Spanish in school at that point and wanted to practice. Berlin was because I was interested in Cold War and WW2 history (the former was mostly from playing Call of Duty).

Paris just happened to be the most interesting other option that fit with that rotation. I went to Paris with no expectations of what it was like, and ended up enjoying it because it was Paris. Before I went, and during my time there, I studied French intensively, even during my lectures when I was supposed to be listening. Here are two of my blog posts that detail my journey.

I learned most of my French in Paris, but it wasn’t Paris or France that motivated me to study French in the first place. And it isn’t the only reason I continue to study French. In addition to la Métropole, there are three places in North America that have a connection to France that pique my interest in the language and its close relatives: French speaking Québec, Acadian/Cajun French speaking Louisiana, and Haitian Creole speaking Haiti

Québec

I grew up in western NY about 2 hours from the Canadian border. My part of NY is culturally similar to Ontario, to the point where Americans from other parts of the US joke that we’re “basically Canada.” The parking lots of the ski resort I grew up skiing at (Holiday Valley) were half full of Canadian license plates.

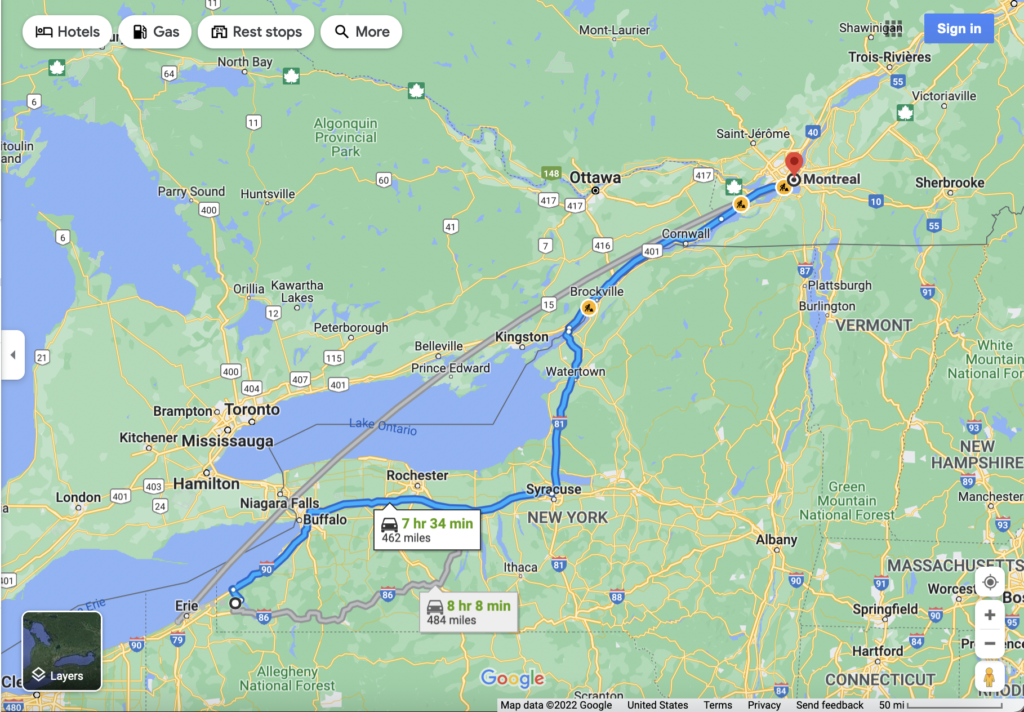

So I thought I knew Canada. But it wasn’t until I was 15 that I learned that there was an entire part of Canada that spoke French and I was floored. Canada was basically my backyard – and you’re telling me you had native French speakers there? I had spent my entire life up until that point thinking that the closest sub-national or national entity to me that spoke a language other than English was Mexico – not Montréal, a place that was only a ~7 hour drive.

I was fascinated by Montréal and Québec, and went there with some friends the summer after high school. It was wild. It was like if Chicago or another other post-industrial North American city spoke French. I still can’t get over it. When we were there, it became quickly apparent that my one friend who studied French couldn’t use it in real life and we faced language barriers. So, that’s when I decided I wanted to learn French, and my sejour in Paris seemed like a great time to learn.

Over the years, I learned more about French-Canadian culture, and found some movies and music that I really liked. Here are some of them:

La Louisianne

After coming back from Paris, I struggled to keep up my motivation to learn French. I had no real cultural connections to France. France doesn’t factor in my day to day life, nor do I know anyone who speaks French, nor are French speaking people’s prominent in my country’s contemporary life like Spanish or Chinese speakers. Even Montréal, which I was fascinated with, seemed less interesting.

I thought to myself – if I didn’t want to lose the French I gained, I had to find a way to make it relevant. So I looked back at American history, and tried to find a place where the French language was prominent, and settled on Louisiana.

If you didn’t know – in 1960 there were 1 million native speakers of French, which isn’t that long ago. The presence of French in (southern) Louisiana dates back to Le Grand Dérangement, when the British deported French speaking settlers from a region formerly known as Acadia in the present day Canadian Maritime provinces (Acadian is where we get Cajun, from acadien or cadien).

By —Angr – Own work. Data from the MLA Language Map Data Center (based on the 2000 U.S. census). Base map is Image:Acadiana Louisiana region map.svg., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1837900

From these Cajun settlers, and a variety of Spanish and African influences we get the vibrant culture of New Orleans. Unfortunately, Cajun French is endangered. English only efforts starting in the 1920s proved to be successful, and now there are only an estimated 150,000 – 200,000 mostly elderly speakers of Cajun French. Those who learn French in Louisiana usually learn Standard French, which is considered the prestige dialect.

There are efforts to revitalize the language, and one organization tasked with that (CODOFIL) created this adorable Cajun French kids series:

Haiti

So Louisiana ended up being a good example of French culture in the US, but it isn’t a place where French is used as a daily language, and the language itself is somewhat endangered. I wanted to find another connection between North America and France. New Orleans and southern Louisiana received migration from the la Caraïbe, in particular from the former French colony of Saint-Domingue, now better known as Haiti. That’s where I looked next.

To be abundantly clear, Haiti’s connection to France is not a positive connection. France colonized Haiti and stole and enslaved people from Africa to work on plantations in brutal conditions, with one of the highest mortality rates of New World colonies. After enslaved Haitians won their independence in 1804, France responded by placing punitive debts on the country that were later absorbed by the United States. Haiti only paid off the debt in the mid 1950s, and this debt is largely responsible for Haiti’s slow development.

Because so many enslaved Africans died under French rule, they had to constantly steal more people from Africa to keep up the labor force. This meant that enslaved Haitians didn’t end up learning standard French, but rather mixed French with their native languages (mostly belonging to the Fon language group of West Africa), creating a creole language.

Creole languages arise when two groups of people who don’t share a common language create a hybrid or pidgin language to communicate. This pidgin language contains elements of both languages, usually with simplified grammar. Once that pidgin language is taught to the next generation, and its spoken natively, it becomes known as a creole language. Haitian Creole, is the world’s most world’s most widely spoken Creole language.

Haitian Creole is not French. But most of the vocabulary dervies from French, so if you speak French, it’s easier to pick up. Many educated Haitians also speak French, so it’s a useful way to learn more about the island.

Haitians have figured prominently in the history and culture of the US/Canada. Many notable North Americans, including Kaytranada and W.E.B. Du Bois are Haitian. In part due to the connections between Haiti and North America, especially North American pop/house music, Haitian music slaps. Here are some of my favorite Haitian songs: